As I write this, it is November 11, 2020. It is approximately six months later than we’d hope to start this series, which is something I now lovingly call “pandemic time.” That is, nothing happens as planned or on schedule in this pandemic. Today is Veteran’s Day, a day we remember people willing to face their own mortality in order to serve a nation and democracy they believe in. It feels like an auspicious day to get started.

The impetus for this blog series came in May of this year, after the sequential and highly publicized murders of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and George Floyd. I say highly publicized because according to data culled from Mapping Police Violence and The Washington Post, police in the U.S. killed 164 black people in the first eight months of 2020. So while names like Breonna Taylor, George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery (who was not killed at the hands of police but was the victim of murder based on race, bias, and assumption) entered the living rooms of American citizens, their deaths appear as only the tip of a lethal iceberg.

Our work centers around the lives of young adults: their longing, their fears, their spiritual questions and pursuits, their yearning for community, their hopes for justice. Our goal is to connect the questions and needs of their hearts to the active and emerging work of American churches. How are we serving their needs? How are we allies in the quest for justice? How are we listening and learning from them? How have we failed and where are we called to repent and pivot in our desire to serve all people, of all races and generations? How can we work together to help birth a world that resembles the one Jesus modeled in the Gospels, aligned with marginalized people rather than principalities? How can our ancient traditions and current practices serve in each person’s healing and the healing of the world?

By the time we were three months into the pandemic, and the economic and racial disparities in our country were quickly and deftly laid bare, we began to key in on a pervasive recognition that both the pandemic and the racial reckoning called up in many of us, and particularly among the young adults in our midst: The truth of our own mortality. The harsh reality that, whether we know it or not, death is always with us. And acknowledging that both COVID and police violence bring the presence and possibility of death into black and brown communities disproportionately.

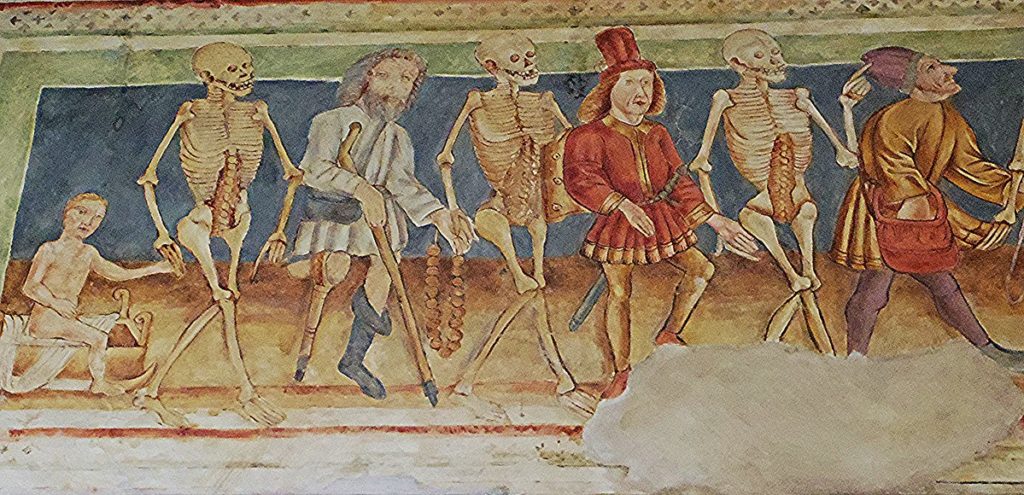

In the middle ages, one of the ways people normalized the presence of death in their daily lives was through art. A genre, often referred to as Danse Macabre (or Dance of Death), emerged to “remind people of the fragility of their lives and how vain were the glories of earthly life.” (Wikipedia by way of the Catholic Encyclopedia). Often the pictures showed a personification of death summoning representatives from all walks of life to dance along to the grave, signaling both the inevitability and the great equalizer of death. We adopted this theme to reflect on our mortality, as well as the reality that, in our current systems and institutions, death is not always an inevitable equalizer. The 787 Collective asked a small group of young adults to consider this topic and share their personal thoughts and reflections. Their responses are as diverse as their viewpoints, and we are deeply grateful for their gifts of poetry, personal reflection, essays and remarks as we all seek to broaden our understanding of each other’s lives during this time and discern the collective call that emerges as we listen to the lives of young adults.

MLC